Why change cannot be managed

Because change is emergent, we have to let go of the illusion of control.

In the business world, change management has become a ubiquitous term, a staple of consulting frameworks and organisational strategies. It conjures images of carefully laid-out plans, workshops, and roadmaps designed to usher in transformation. Yet, as my esteemed colleague and friend Richard Knowles observes:

“Change comes out of the work itself as people co-discover new ways to work together. Change is an outcome. Imposing change as an input rarely works.”

Dick Knowles on LinkedIn

This simple, yet profound insight invites us to reconsider the very premise of change management.

Change, as both a process and an outcome, is not something that can be engineered or imposed. It is a natural by-product of human interaction, a continuous, emergent process that unfolds as people adapt to new realities and co-create ways of working. To understand this, I would like to draw on the work of the late Ralph Stacey and his theory of Complex Responsive Processes of Relating, which offers a more nuanced and realistic view of how change happens in organisations. People that have been following this Substack have read about Ralph’s profound insights multiple times before.

The Fallacy of “Managing” Change

The phrase “change management” implies control—a notion that change can be directed and delivered like a project. Organisations often adopt structured methodologies to manage change, with clear objectives, timelines, and deliverables. However, these approaches overlook the inherently unpredictable and relational nature of human interaction. People are not machines, and organisations are not static systems waiting for external inputs to produce desired outputs.

Case Study: The Merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham

When two pharmaceutical giants merged to form GSK, leadership approached the integration with a heavy reliance on top-down management. The change strategy focused on aligning processes and systems, assuming people would simply adapt. However, resistance quickly emerged as employees felt overlooked and excluded from the process. Recognising this, leaders shifted their approach, engaging employees in open forums to co-create integration strategies. This participatory approach allowed for emergent solutions, resulting in a smoother transition.

Stacey’s Complex Responsive Processes of Relating

Ralph Stacey’s work provides a lens through which we can better understand the dynamics of change. Stacey argues that organisations are not predictable, mechanistic systems but complex, adaptive processes shaped by ongoing interactions between individuals1. He emphasises that:

1. Change is Emergent: Change arises from the everyday interactions between people as they negotiate meaning, adapt to new circumstances, and respond to challenges. It cannot be predetermined or controlled in a linear way.

2. Relationships Matter: The quality of relationships within an organisation plays a crucial role in how change unfolds. Trust, dialogue, and mutual understanding create the conditions for people to co-discover new ways of working.

3. Uncertainty is Inevitable: Attempting to eliminate uncertainty through rigid plans is futile. Instead, leaders must embrace uncertainty as a space for creativity and innovation.

Case Study: Zappos’ Holacracy Implementation

Zappos adopted holacracy, a decentralised management system, in an effort to foster innovation. The initial rollout faced significant resistance and confusion as employees struggled to adapt to the new structure. Over time, however, the company abandoned strict adherence to holacracy’s principles and allowed teams to experiment with variations that worked for them. This emergent approach led to a hybrid model that better suited Zappos’ culture, demonstrating how change arises through ongoing interaction rather than rigid implementation.

Change as an Outcome, Not an Input

As Dick Knowles aptly puts it, Change is an outcome. It is not something you can inject into an organisation like a vaccine; it is the result of people working together, learning from each other, and discovering new possibilities. This perspective shifts the role of leaders and managers. Instead of trying to “drive” change, their role is to:

• Create Space for Interaction: Facilitate environments where people can engage in meaningful conversations, share ideas, and experiment with new ways of working.

• Nurture Relationships: Build trust and foster a sense of psychological safety so that people feel empowered to explore and adapt.

• Stay Present in the Process: Instead of focusing on long-term outcomes, pay attention to the present moment and the small, incremental shifts that are already occurring.

Case Study: Toyota’s Continuous Improvement Culture

Toyota’s famous “Kaizen” philosophy demonstrates that change is an outcome of sustained, everyday improvements. Instead of imposing top-down directives, Toyota empowers employees at all levels to suggest and implement small changes to improve processes. This continuous improvement culture has been the cornerstone of Toyota’s global success, showing how change emerges naturally when people are given the tools and trust to innovate.

The Pitfalls of Imposed Change

When organisations attempt to impose change, they often encounter unintended consequences. For example:

• Resistance Becomes Entrenched: People may comply outwardly but disengage inwardly, leading to superficial adoption rather than genuine transformation.

• The Illusion of Progress: Metrics and milestones may give the appearance of success, but the deeper cultural and behavioural shifts needed for lasting change are absent.

• Missed Opportunities for Innovation: By sticking to rigid plans, organisations may miss the chance to adapt to unforeseen opportunities or challenges.

Case Study: Microsoft’s Shift to Cloud Services

When Satya Nadella took over as CEO of Microsoft, he faced resistance to shifting the company’s focus from traditional software to cloud services. Instead of enforcing a top-down mandate, Nadella encouraged open dialogue across teams and gave them autonomy to experiment. By focusing on relationships and creating space for co-discovery, Microsoft successfully navigated a major cultural shift and emerged as a leader in cloud computing.

Embracing Emergent Change in Practice

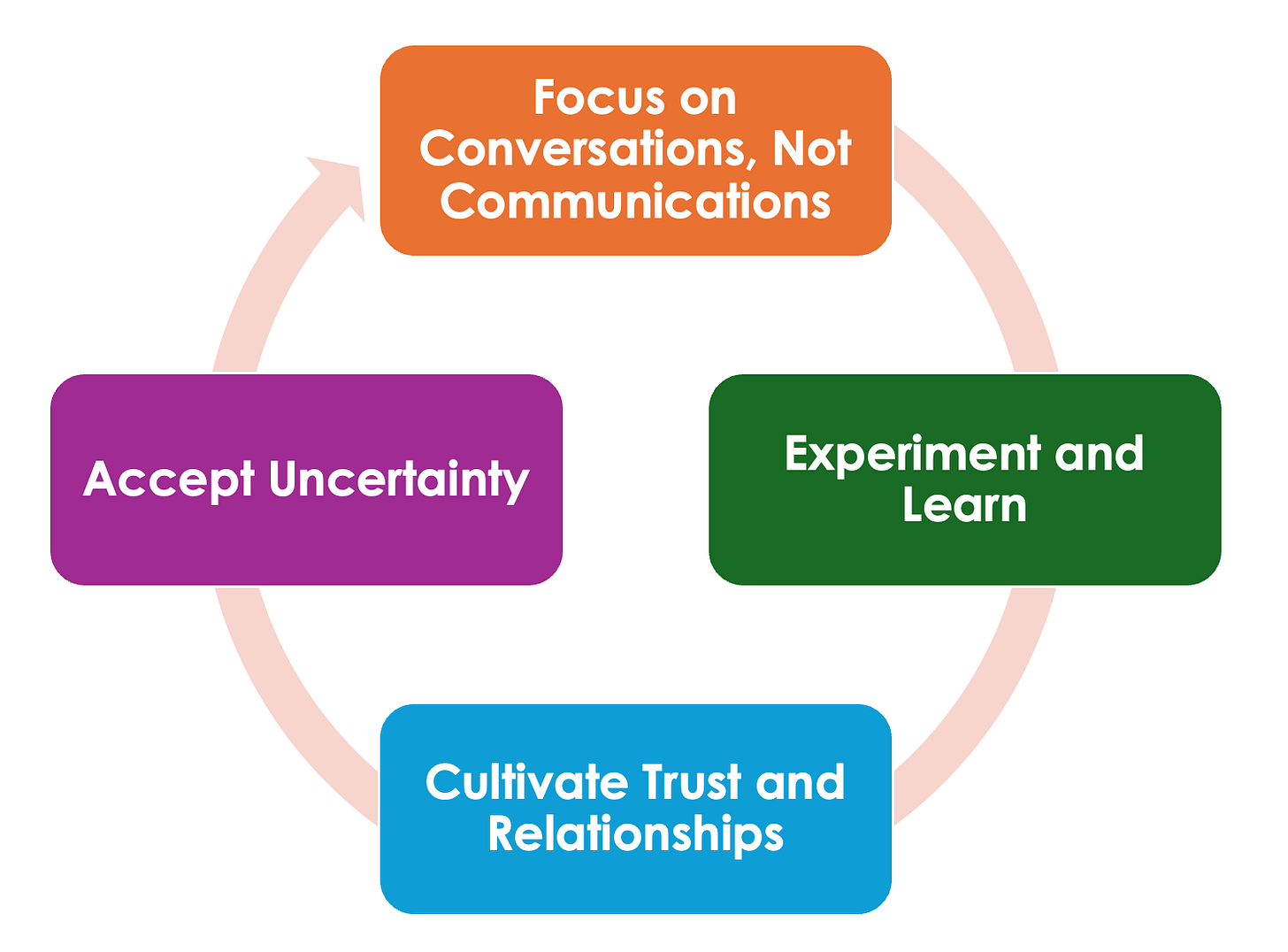

How, then, can organisations embrace the emergent nature of change? Here are some practical principles.

Focus on Conversations, Not Communications

Traditional change management often centres on top-down communication—leaders telling employees what will happen and when. Instead, organisations should prioritise dialogue. Genuine change emerges from conversations where people can voice concerns, share insights, and co-create solutions.

Case Study: Burberry’s Turnaround

When Angela Ahrendts became CEO of Burberry, she initiated a cultural transformation by hosting listening sessions with employees at all levels. This open dialogue allowed the company to identify key barriers to success and co-create solutions, leading to a dramatic turnaround.

Experiment and Learn

Instead of implementing large-scale change all at once, organisations can experiment with small changes and learn from the outcomes. This iterative approach mirrors Stacey’s idea of navigating complexity by staying attuned to what emerges.

Case Study: Google’s “20% Time”

Google’s practice of allowing employees to spend 20% of their time on personal projects led to innovations like Gmail and Google Maps. This approach fostered emergent change by giving people the freedom to experiment and adapt.

Cultivate Trust and Relationships

Change requires a foundation of trust. When people feel valued and respected, they are more willing to engage in the messy, uncertain process of adaptation.

Case Study: Patagonia’s Employee Engagement

Patagonia’s commitment to environmental values is reflected in its workplace culture. By fostering trust and encouraging employees to bring their values to work, Patagonia has created a resilient organisation capable of adapting to challenges.

Accept Uncertainty

Leaders often feel pressure to have all the answers, but in a complex world, this is impossible. Embracing uncertainty allows organisations to remain flexible and responsive.

Case Study: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan

Unilever’s ambitious sustainability goals involved navigating significant uncertainty. By focusing on experimentation and collaboration across teams and stakeholders, the company made meaningful progress while staying adaptable to changing circumstances.

Redefining the Role of Leadership

In a world where change is constant and unpredictable, the role of leadership must evolve. Leaders are no longer the architects of change but facilitators of emergence. This means:

• Listening More Than Telling: Paying attention to what is happening on the ground rather than dictating solutions.

• Empowering Teams: Giving people the autonomy to experiment and adapt within a clear framework of shared values and goals.

• Staying Humble: Recognising that leaders don’t have all the answers and being willing to learn alongside their teams.

Conclusion: Letting Go of the Illusion of Control

The idea of “managing” change may provide comfort in its promise of control and predictability, but it is ultimately a contradiction. Real change is emergent, relational, and unpredictable. By letting go of the illusion of control, organisations can create the conditions for genuine transformation to occur.

As Ralph Stacey’s work reminds us, and as Dick Knowles so succinctly puts it, change comes from the work itself. It is an outcome of people co-discovering new ways to relate and work together. When organisations embrace this reality, they move beyond managing change to living it. And in doing so, they unlock the true potential of their people and their systems.

I have outlined my own journey to understanding business change, by embracing Stacey’s new ways of seeing in this article.

I've always thought Change Management is a misnomer. I prefer to call myself a change catalyst. But really it's the key stakeholders who need to be change makers.