How my evolving way of seeing organisations changed my business change practice.

There are different ways we can think about organisations. But how we choose to do that, affects what we actually see. This is my personal journey in thinking about business transformation.

This is a for me unusually long article, but it sets out my personal journey as a business change and transformation consultant. By sharing this experience, and drawing attention to what were some key insights for me, I hope to contribute to the conversations around how we best think about, and engage with, organisational change.

How we look at things matters

An astronomical amount of content is being created over the years on many, many different platforms, aimed at helping people make sense of their world. Make sense of the challenges and opportunities that seem to present themselves at, perhaps, an ever-increasing pace. This is as true for business as it is for any other aspect of our lives. And, in this Substack, even I am talking about management, leadership, business models, transformation and change, and so forth and so on.

The intention of all this information is usually to offer insights that may create new or different ways forward to those where the content is aimed at.

But very much like the Lost Property/Objets Trouvés image in last week’s article how we perceive the information is very dependent on our own background and context of where we are at the time of receiving and/or processing it.

So, how does our own background and context affect what we can learn (or not) from all the, usually well-meant, content aimed for our consumption?

A good, challenging question.

The purpose of this substack is to help people make (more?) sense of their business life by engaging in pragmatic and practical conversations, or so the title of it makes us believe. It seems appropriate, therefore, to take this challenge on, and throw my own practical reflections in the mix.

And this week’s (rather long) reflection is on that how we choose to look at business organisations -what our own mental model of them is, if you like - affects not only how we make sense of that content, but even what we actually see.

The illustration (from a New Yorker article) that I selected to accompany this article above shows that, if we choose to use some clever trickery (in this particular case with ingeniously piling up some items and use directed light to create a shadow), we can even make a collection of lifeless items we find on our desk look like a wonderfully intimate picture of a woman and her child. But let’s be clear: it’s only because we want to see this, we see the mother and child. And, of course, the context of us reading this New Yorker piece with the title Are you my Mother? makes this almost imperative. But this is a pivotal insight.

INSIGHT 1 - How we choose to look at something in our day-to-day context affects what we actually (are able to) see.

This insight resonates with my day-to-day experience in how one can look at business organisations.

I am a member of the UK-based HiveMind Network and this week a few of us were invited to present and discuss our personal experiences. In this case, I shared how my way of looking at organisations affected my own consulting practice over the years. This article is a more detailed description of what I talked about there.

I will discuss here 3 different ways to look at organisations, what they can tell and teach us, but also what their limitations are. It will help understand my personal journey (if you would be interested in that) but, more so, I hope that the insights of my experience can support your own understanding how your own ways of seeing, your mental models, affect your sense making. These mental models act as metaphors to help shape the way we think. See for instance also the mountain analogy I referred to in an earlier article.

The three models I will discuss here are of course not the only models, but for me, they logically evolved from one into the other.

These models are deliberately portrayed as extremes. Nothing is black and white, of course, but exploring these extremes, gives us potentially valuable insights.

The models are:

Seeing organisations as machines

Seeing organisations as systems

Seeing organisations as groups of interacting individuals

Let’s dive in.

Seeing Organisations as Machines

I started my professional practice as a business change consultant in 1996 with (what then still was) Price Waterhouse Management Consulting Services, PW, based at London Bridge, London. Later they became PricewaterhouseCoopers, PwC, and then eventually -after my time there - sold on to become IBM Consulting.

This is the late 90s and the business world was big time into Business Process Modelling as the overarching paradigm in consulting. Our clients were encouraged to see their organisations no longer as functions and procedures, but as business processes that aimed to achieve value add.

The very nature of business processes is the notion that our day-to-day work can be mapped in logical steps of cause and effect. This way of seeing has important benefits. After all, you are creating a common language and view. A language using mechanical terms very much like we talk about machines. This means you can redesign those business processes by eliminating non-value add steps, map data and systems flows and then design and implement systems to automate the processes where possible. Indeed, BPR (Business Process Re-engineering) and BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) were the buzzwords of the 90s. It launched my career as a business change consultant to help people through the associated change. And, because in PW/PwC we worked with many clients in many industries, it allowed us to gather, develop and identify what were best practices1 to execute these processes.

INSIGHT 2 - Seeing organisations as machines can help us optimise the ways we work by logically re-engineering key processes and adopt good practices that have worked well elsewhere.

As business change managers, our job is to help clients manage the changes to go from one way of working to another. In PW/PwC our Change Mentor methodology was built in this mechanical model of organisations. Language, again, is important, and the Change Mentor methodology talked about Change Levers. A Lever, of course, is a very mechanical concept, suggesting that if I pull the lever, something else will happen, usually in a linear way. The typical cause and effect logic of a world where we see organisations as machines. At the time, these levers were things like Systems, Process, People, Data, etc. Change plans tended to be focused on these levers.

INSIGHT 3 - When there is a linear cause and effect relationship between activities that we undertake and their consequences, the mechanical language works very well.

Also, if you are designing a machine, you had better think of everything, because the machine cannot think for itself. Of course, in some cases, organisations do act enough like machines to justify selected use of this metaphor. For example, if I am having my gall bladder removed, I would like the surgical team to operate like a precision machine, please.

INSIGHT 4 - If the required activity requires strict and carefully controlled ways-of working (like in outsourcing situations), the machine metaphor is a perfect analogy for dealing with those challenges.

And this view indeed works well, until you run into situations where A does not cause B, but can lead to multiple outcomes, work back on itself and so on. If the outcome doesn’t linearly flow in the direction we expect, we need to manage the subsequent issues. We needed to align the ways of working between the different stakeholder groups to be able to implement the required changes. Change Plans became complex and, because people did not understand what was happening, they therefore did not act as expected. The notion of Change Resistance emerged that -in turn - needed managing. And, so it seems, more and more of the work people did not seem to adhere to the linear model.

INSIGHT 5- When there is no obvious linear relationship between cause and effect, the machine metaphor doesn’t work anymore and will cause misunderstanding, frustration and resistance in the organisation.

Experiencing this in client environments drew me (and many others) to a different way of seeing that seemed to deal with that misalignment (linear pun intended).

Another consequence of the linear way of seeing, is that people see themselves to be cogs in the machine, doing ever better what they need to do in their own little silo, but not knowing how what they are doing affects the whole of the organisation. Often even, built-in organisational barriers, intentionally or not, actively inhibit cross-functional collaboration, because the aim is running one’s own process optimally and then hand-over to others. This leads to another important insight.

INSIGHT 6 - Focusing on optimising parts of the organisation separately, inhibits cross-functional optimisation and creativity.

Seeing organisations as systems

Searching for new ways of looking at organisations, led me in the early 2000s to systems thinking. After all, if the linear, mechanical model seemed to cover only a limited amount of the work we do, we need to look for non-linear models.

Many people started to talk about organisations as organisms, rather than machines. They therefore started to look at ways to compare organisations to natural systems that had been studied in the complexity sciences. Indeed, this journey led me to study complexity science (an MA in Complexity, Chaos and Creativity at the University of Western Sydney, Australia) and see what insights I could gain for the human organisations I worked with in my practice.

In natural systems, a very useful idea has been the definition of these bounded systems as complex adaptive systems (CAS). The theory being that because of the complex interactions the system is coupled to the external environment (perhaps via semi-permeable boundaries) so that they adapt to it. Thus viewed, each system is nested in a larger (higher) system.

From there, it is a small step to then see human organisations as systems and consequently as complex adaptive systems, in parallel with the natural sciences.

The metaphors can provide powerful ways to look at human organisations. The principles of self-organisation, emergence, edge of chaos, etc., from the complexity sciences can provide interesting new insights in issues that organisations face. Given the constant struggle in business organisations to find ways to cope with the inherent uncertainty they face, these then relatively new theories helped us to make sense.

For instance, rather than defining a project plan into the finest details, we can choose to hold sessions with representatives from all affected functional and non-functional teams to collectively determine the 3-5 key challenges we face (how we might go about that is for another article).

Let’s call those eventually selected challenges Big Rocks.

Then ask these people in that meeting to self-organise around those issues that they themselves feel they can best contribute to by providing them with some simple instructions.

INSIGHT 7 - Allowing the people to self-organise around an issue they feel strongly about, means their discretionary energy will flow to that work, rather than them resisting to tasks that a manager would assign them to.

The simple instructions mentioned could be something like:

Your Big Rock Team has a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 5 people

Get clear on what is/are the issues around this Big Rock

Determine what the steps are that will be necessary to think about or to do with respect to the issues

Is there a priority/priorities?

Are there Alternatives to consider?

Are there any other people in the organisation you need to involve in this Big Rock work?

Plan out the Process on how your Big Rock team is going to tackle this:

What are the concrete things that you will do (What, Why, When, How, Who, Timing, etc)

When will your team next meet to resolve this Big Rock?

Who would you suggest is your Sponsor for this work?

It goes without saying (but let’s say it anyway) that management needs to support the work plan they come up with. The role of the sponsor is to ensure this happens coherently.

INSIGHT 8 - By giving the teams space to draw their own plan and ways of working, they will generate the required outputs in an emergent way, and based on what they know they can do, whilst at the same time executing their day-to-day work.

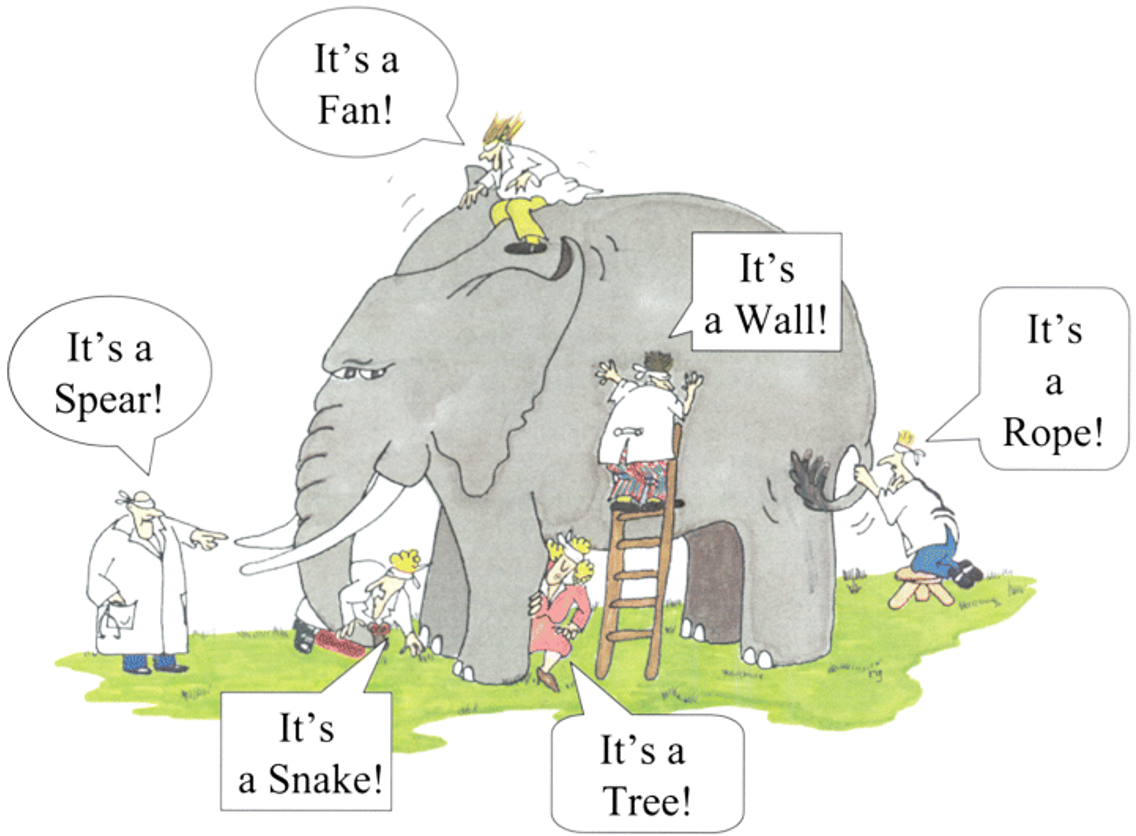

Further, when addressing complex issues, rather than define them as closed problems of several, separate issues within our own organisational unit, we can encourage cross-functional conversations to focus on the whole. Very much like the Hindu parable of the 6 blind (wo)men and the elephant.

This parable addresses the situation that if we let each blind (wo)man define what this thing called An Elephant is, depending of where they reside and what they feel when they touch the Elephant, they will define it as something different. And all would be totally wrong. The analogy is of course that while a project team might see the Elephant, the constituent parts of the business might not.

So, the questions that come to mind would be:

How can we make the business see our (beautiful and healthy!) Elephant

How do we ensure our project teams keep their eye focused on the Elephant and not on how (perhaps) the business wants us to define it

INSIGHT 9 - When discussing a project, ensure that every participant understands what we try to do together (understand what an Elephant is), rather than focus on its constituent parts

These are all good insights. But, as with every metaphor, there is a real risk that we start equating the organisation with that metaphor. Indeed, it wasn’t long after that the systems thinking was introduced that people started to say that an organisation really is a CAS. Which of course it is not.

INTERMEZZO - BOIDS

In 1986 the American artificial life and computer graphics expert Chris Reynold developed an artificial life programme called Boids. Boids simulates the flocking behaviour of birds on a computer screen. He did this by programming the (in simplest version of his) boids with only one set of three very simple rules:

separation: steer to avoid crowding local flockmates;

alignment: steer towards the average heading of local flockmates

cohesion: steer to move towards the average position (center of mass) of local flockmates

The emergent, complex!, behaviour observed on the screen was indeed like birds flocking.

A nice, more complex, version can be seen here.

Because these Boids were so elegant and their complex behaviour was so compelling, it was concluded (wrongly of course) that, since organisations are Complex Adaptive Systems, their complex behaviour therefore would emerge from simple rules. Therefore, what we needed to do was to just find the correct set of simple rules and, voila!, the required behaviour would emerge. It was a small step to equate these simple rules with organisational values and the objective became to define the organisational values that would make the desired behaviour emerge.

This is of course wrong on so many fronts, but in its own dogmatically contained theoretical framework, very compelling. When I heard my fellow complexity practioners starting to talk this way, I started to see I was on the wrong path. The theory had become a dogma.

Let’s break the main issues down:

The boids are, of course, not flocking birds at all. They are blibs on a computer screen. Our brains will call their behaviour flocking because it has evolved to name patterns, even when they are just blibs moving on a screen.

Real birds, not unlike people, are much more complex than blibs on a screen. They have feelings, thoughts, thirst, hunger and so on. Blibs don’t.

Organisations can be seen as a CAS, but it’s just a metaphor, an analogy that can give us insights about our organisation, but nothing more.

INSIGHT 10 - Systems thinking can give great insights, but when taken the systems analogy for organisations too far and start equating organisations with complex adaptive systems, the wrong conclusions will be drawn.

Because this all happened during me doing my complexity degree, I was lucky enough to meet certain people that had recognised this as well and helped me steer in a new, much more satisfying direction.

Seeing organisations as groups of interacting individuals

Amongst the wonderful people I met, was the late prof. Ralph Stacey at the University of Hertfordshire and his colleagues at the Complexity and Management Centre in the UK.

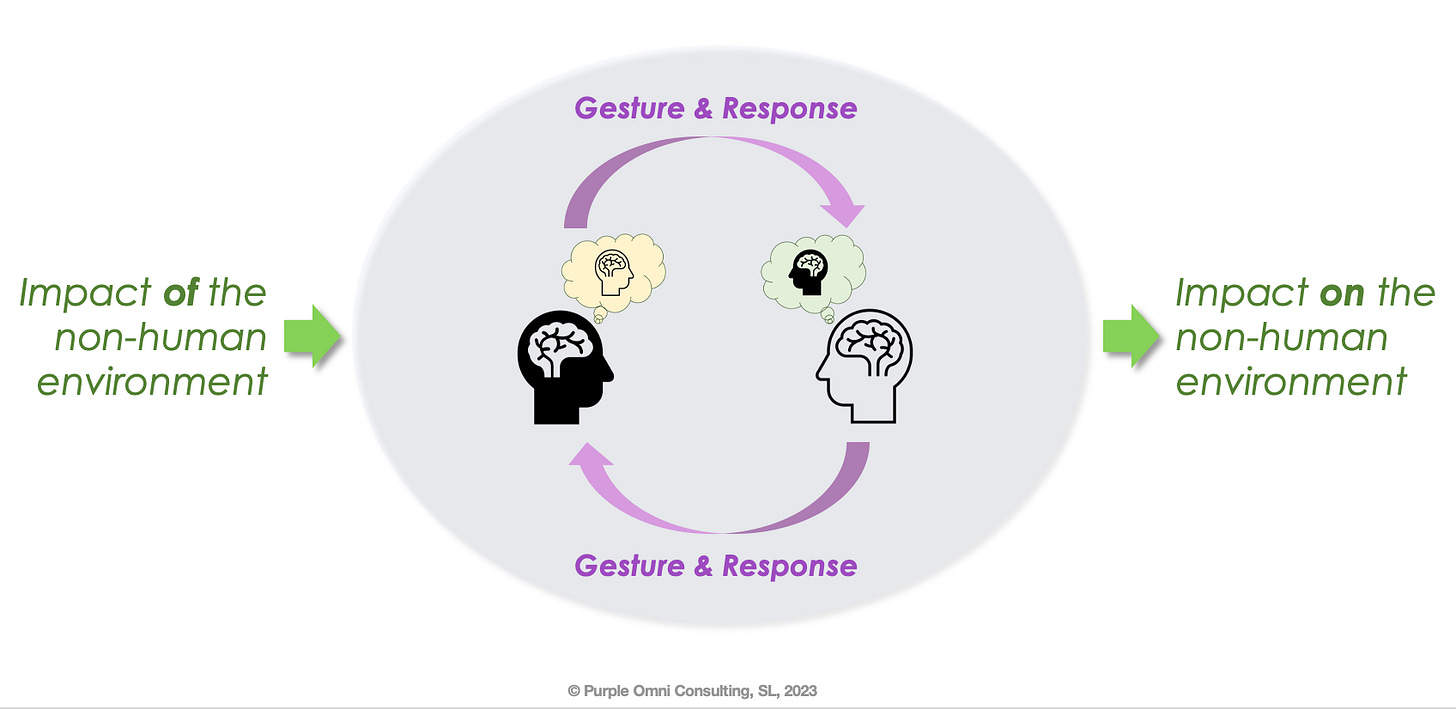

The great shift in thinking from Ralph and the team was to start at the point of what we know about organisations and build it up from there. And what we know from our own direct observations, is that organisations consist of people that are continuously interacting. So, rather than try to see them as machines or organisms or systems, he suggested to pay attention to the processes of interaction that we know and see are happening in human organisations. Ralph demonstrated that these processes consist of the narrative-like sequences of gesture and response between human bodies2. In these interactions, people continuously reinterpret their own experiences in order to act (gesture) to achieve some future expected state. This expectation, in turn, feeds back on their interpretation of their past experiences. Each gesture triggers a similar process in other people who then respond with a new gesture. And these gestures and responses, could be verbal, non-verbal, conscious or unconscious. With so many interactions that are happening all the time, this is a highly complex process, and hence the wonderful term complex responsive processes of relating. See the following image.

With continued interaction, as is of course happening in organisations, some common themes will start to emerge. These themes emerge because of a common intention of the future is discovered in conversation. Because we are all different, real and existing differences in experience and intentions exist, as well as real and existing issues that need resolving in order to achieve the common desired future. This emergence is self-organising in nature. And, by drawing attention to those emerging themes, we can start to create positive change, This is where insights from complexity theory proved to be very helpful to me, indeed.

Awareness of these processes, will make us choose to interact in new ways to achieve our own desired outcome.

INSIGHT 11 - By actively engaging in the many conversations, formal and informal, that are happening continuously in our organisations, and drawing attention to emerging common themes, we introduce the possibility to create new insights and actions.

It is this insight that helped me understand the importance of conversations in organisations. So much, that it actually made me see organisations as continuously evolving conversations and this leads me to the final, and for me pivotal insight:

INSIGHT 12 - Organisational change can be seen as changing the conversation in conversations.

Does this long story make sense?

How do you see organisations?

What insights can you share from your experienes?

My personal view is that Best Practices is a misnomer. How do we know they are best? I prefer the term Good Practices, but that’s not the subject of this article

Stacey, R. (2000). Complex Responsive Processes in Organisations, London: Routledge

This makes a lot of sense to me, and echoes some of the methodologies I have come across in my career in CM. I have taken a less academic route (your studies sound fascinating) - but it's interesting that living abroad and travelling experiences have led me to some similar conclusions about the nature of change and human interactions.