We are dancing on a pin's head!

Insights on how to navigate the eternal tension between change and stability

In the fast-evolving world of business, leaders face an ongoing challenge: how to strike the right balance between the need for change and the necessity for stability. Organisations must adapt to survive in dynamic markets, yet they must also maintain the core aspects of their identity and operational continuity to ensure ongoing success. This balance is not easily achieved, and navigating it often requires a thoughtful and strategic approach. Our challenge is to come up with a practical approach to find that delicate balance, without it becoming an academic exercise with endless models and discussions, as so often happens in business essays. Here, we aim to dance on that delicate pin’s head, without this article becoming a futile discussion about

“How many angels can dance on a pin’s head?”1

At Purple Omni Consulting, we specialise in change and transformation, recognising that successful business evolution is not about abandoning stability but about integrating change with a solid foundation. One concept that aligns well with our philosophy is Ralph Stacey’s Complex Responsive Processes of Relating (CRPR). Stacey’s work offers a lens through which leaders can better understand the unpredictable and emergent nature of change, and how stability and transformation can coexist. See for instance the story of my personal evolution in understanding business change.

This essay explores how business leaders can leverage both the principles of change and stability using Stacey’s framework, alongside the practical tools and strategies we offer at Purple Omni Consulting, to successfully navigate the complexities of modern business environments.

Understanding the Dichotomy of Change and Stability

To begin, it is crucial to understand why the balance between change and stability is so challenging. On one hand, businesses must continually evolve to stay competitive. Technology, market trends, and customer expectations are in constant flux. Companies that resist change risk becoming obsolete, overtaken by more agile competitors. For example, Kodak, once a giant in the photography industry, failed to adapt to the rise of digital photography and was quickly left behind. Similarly, Blockbuster Video did not evolve with the digital revolution in entertainment and was replaced by companies like Netflix that embraced streaming technology.

On the other hand, businesses need a stable foundation – a strong sense of purpose, effective processes, and cohesive culture – to maintain trust with customers and employees and ensure efficient day-to-day operations. Stability helps avoid chaos in decision-making and keeps teams aligned with the company’s mission. For instance, companies like Johnson & Johnson have maintained a clear, stable corporate culture based on values such as integrity and patient safety, which has helped them weather crises and maintain public trust over the years.

This dichotomy creates tension. Leaders often feel pulled between pushing for innovation and maintaining the status quo. Too much change can lead to instability, confusion, and burnout. For example, constant restructuring without clear communication can make employees feel insecure about their roles. On the other hand, too little change can lead to stagnation. Nokia, for instance, was slow to adapt to the smartphone revolution, sticking too long to its established mobile phone models, and was overtaken by competitors like Apple and Samsung.

Ralph Stacey’s Complex Responsive Processes of Relating

The late Ralph Stacey, a professor of management, introduced the concept of Complex Responsive Processes of Relating to explain how change happens in organisations. Stacey’s theory draws on the principles of complexity science, which examines how systems behave in unpredictable, dynamic environments. Instead of seeing organisations as rigid structures, Stacey viewed them as webs of relationships and interactions, where individuals continuously respond and adapt to each other. A good, albeit poor sound quality, narrative from Ralph himself can be seen here. Worth a watch, if you have the time.

In practical terms, this means that change does not occur because leaders implement a well-defined strategy in isolation from the rest of the organisation. Change emerges from the interactions between people at all levels. Take, for example, the case of Toyota’s famous Kaizen culture, which empowers employees at every level to suggest improvements in the production process. Over time, these small, incremental changes, generated from the bottom-up, have helped Toyota stay innovative and competitive while maintaining operational stability.

This leads to a key insight for business leaders:

Stability and change are not polar opposites. They are interdependent. An organisation is never fully stable or fully in flux; instead, it is in a continuous process of responding and adapting to internal and external influences.

Consider how Google manages to innovate continuously while retaining a strong core business. By maintaining stability in its core search and advertising platforms, Google can simultaneously experiment with high-risk, high-reward projects like autonomous cars and artificial intelligence research through its subsidiary, Gemini.

Leaders must become comfortable with uncertainty and recognise that their role is not to impose change, but to foster an environment where it can emerge naturally.

How Complex Responsive Processes Can Help Leaders

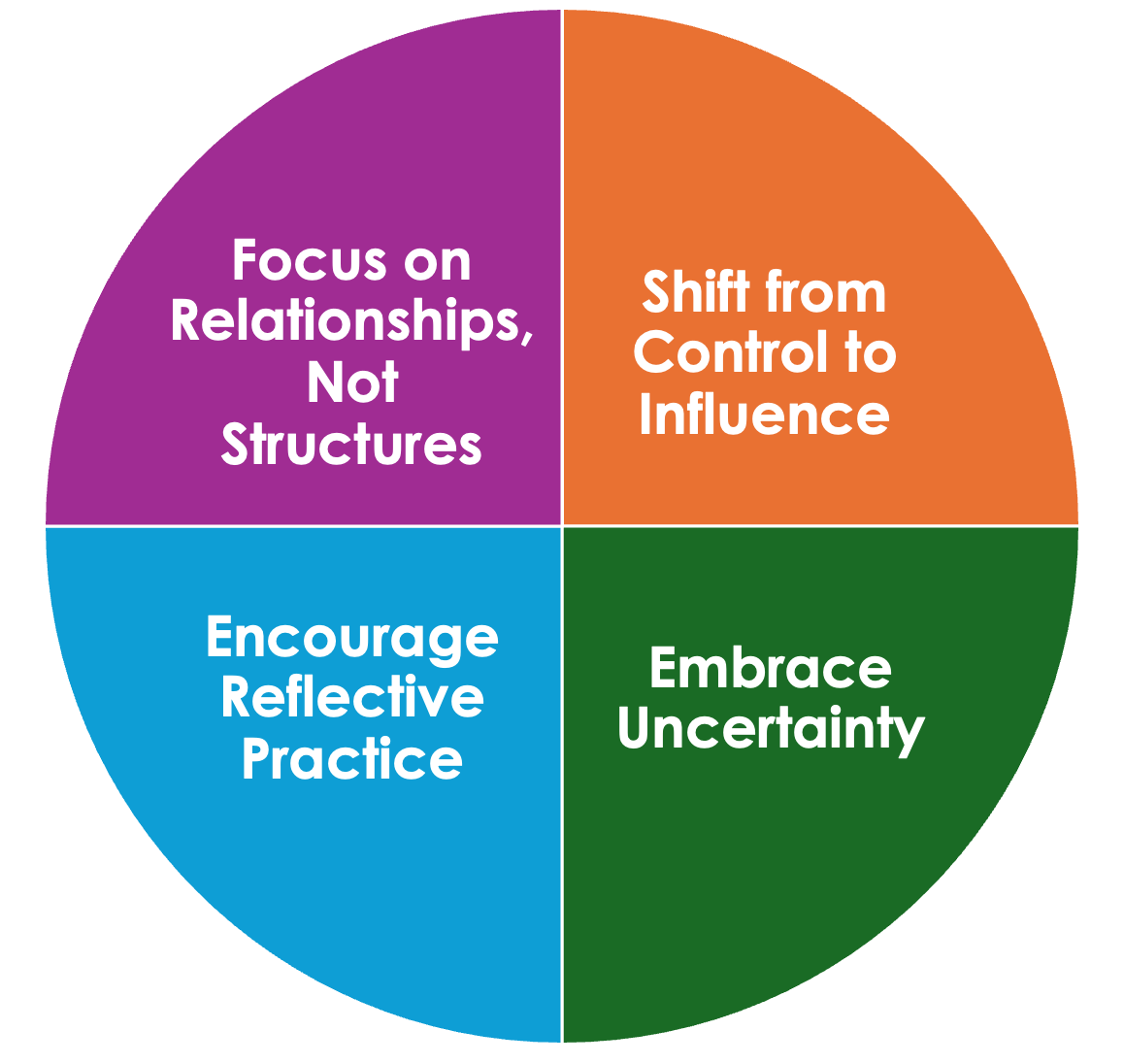

1. Shift from Control to Influence - One of the first challenges leaders face when seeking to balance change and stability is the tendency to want to control the process. Stacey’s framework advises against this. Instead of attempting to control every aspect of change, leaders should focus on influencing the conditions in which change happens. For example, Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, shifted the company’s culture from a competitive, hierarchical model to a collaborative and growth-oriented one. Rather than controlling every new initiative, Nadella focused on fostering a culture of learning and openness, which allowed innovation to emerge across the organisation. This cultural shift helped Microsoft transition from a focus on Windows software to a cloud-first business model, leading to renewed growth.

2. Embrace Uncertainty - Stacey argues that leaders must embrace uncertainty rather than fear it. Organisations are complex systems where outcomes cannot be fully predicted. Leaders should accept that they will never have all the answers and that their role is to navigate, not to dictate. A clear example of this is how Spotify has approached its organisational structure through a system known as “squads,” where small, self-organising teams are empowered to make decisions. This model embraces the uncertainty of rapid technological shifts by giving teams autonomy to respond to challenges in real time. Leaders at Spotify focus on setting overall strategic direction but allow the squads to manage the specificities of execution, accepting that not every initiative will succeed but trusting that innovation will emerge from the collective process.

3. Encourage Reflective Practice - Stacey also highlights the importance of reflection. Leaders and teams should regularly engage in reflective practices to understand how their interactions are contributing to both stability and change. For example, companies that engage in regular post-project reviews or “retrospectives” can learn from both successes and failures. This reflective process allows organisations to adapt and iterate, improving over time. The British supermarket chain Tesco, after suffering financial setbacks, engaged in a reflective process that involved reviewing customer feedback and internal practices. This reflection led to the introduction of simpler pricing strategies and a renewed focus on customer service, which helped restore the company’s competitive position.

4. Focus on Relationships, Not Structures - Traditional organisational theories often focus on structures – hierarchies, processes, and systems. Stacey’s theory, however, emphasises relationships. Leaders should focus on building strong, trust-based relationships within the organisation, as these relationships are the foundation of both stability and change. Consider how the founder of Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard, built his company around a set of relationships based on shared environmental values. By empowering employees to make decisions aligned with the company’s mission, he has fostered a stable, value-driven company that also continuously adapts to market demands and environmental challenges. The focus on relationships has helped Patagonia maintain its core identity while innovating in product design and sustainable practices.

Applying These Insights

At Purple Omni Consulting, we believe that leaders can achieve the balance between change and stability by integrating Stacey’s principles into their leadership approach. We focus on helping organisations foster a culture of adaptability without losing sight of their core identity. Some of the ways we support leaders in achieving this balance include:

1. Creating Safe Spaces for Innovation - We help leaders design environments where employees feel safe to experiment, fail, and learn. For instance, we might work with a company’s leadership team to establish internal innovation hubs, where teams are encouraged to prototype and test new ideas. In one case, a client of ours in the retail sector saw success by setting up a ‘sandbox’ where store employees could trial new customer service techniques. These experiments not only encouraged innovative thinking but also fed back into the core operations, creating improvements without disrupting the overall stability of the business.

2. Facilitating Collaborative Conversations- Change often stalls when communication breaks down. We work with leaders to facilitate open, collaborative conversations across all levels of the organisation. One of our clients, a manufacturing firm, was struggling to integrate digital tools into its supply chain. Through facilitated cross-department workshops, we enabled conversations between IT, operations, and frontline workers, helping the company identify practical ways to implement technology without disrupting core operations. This collaborative approach allowed change to emerge naturally and sustainably.

3. Strengthening Organisational Identity - While change is essential, so is stability. We help organisations strengthen their core identity – their mission, values, and culture. For example, we worked with a fast-growing tech company that was expanding rapidly into new markets. While growth was a priority, the company’s leadership also recognised the importance of maintaining the culture that had initially made them successful. We worked with them to articulate their core values clearly and helped them develop strategies to embed these values across all new locations. This gave employees a sense of continuity, even as the organisation went through significant transformation.

4. Developing Adaptive Leadership - Leaders are key to balancing change and stability. We provide training and coaching to help leaders develop adaptive leadership skills. One way we do this is through simulations that allow leaders to experience the complexity of managing change in real-time. In a recent engagement with a financial services firm, we ran a leadership programme that simulated market disruptions, helping executives practice adaptive decision-making. The result was a more resilient leadership team, better equipped to handle both everyday challenges and more significant, unexpected disruptions.

Conclusion: Balancing Change and Stability

The balance between change and stability is not a fixed point but an ongoing process. Organisations are constantly adapting to their internal and external environments, and leaders must be able to guide this process with a steady hand. By embracing Stacey’s Complex Responsive Processes of Relating, leaders can move away from the traditional model of top-down control and instead focus on building environments where change can emerge naturally from within the organisation.

At Purple Omni Consulting, we believe we understand the complexities of change and transformation. We work with leaders to help them navigate this balance, ensuring that their organisations remain resilient, adaptable, and grounded in their core identity. By focusing on relationships, embracing uncertainty, and fostering reflective practices, leaders can find the balance between change and stability and guide their organisations toward long-term success.

So, this is not like the obvious futility of the metaphorical angels dancing on a pin’s head, at all. This is real world stuff, because in a world where change is constant and stability is necessary, the real challenge for business leaders is not to choose one over the other, but to master the art of balancing both.

The phrase is often associated with medieval scholastic debates, particularly with a stereotype of theologians or philosophers engaging in arcane, abstract discussions. The most common version of this concept is the question: “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” However, there’s no direct evidence that this question was actually debated during the Middle Ages. It appears to have originated as a 17th-century satirical attack on scholasticism, which refers to the highly detailed and logical debates pursued by medieval scholars, especially in theology. In business writing, the expression “dancing on the head of a pin” can be applied as a critique of focusing too much on irrelevant details or engaging in excessively complex discussions that don’t add value to the main point or objective. It refers to:

1. Overanalyzing minutiae: Spending too much time and effort on minor or trivial details that don’t contribute to solving a problem or moving a project forward.

2. Unnecessary complexity: Making issues more complicated than they need to be by delving into irrelevant or overly technical points, which can distract from more critical decisions or actions.

3. Pedantic arguments: Engaging in debates or nitpicking over minor points in a document, plan, or strategy that don’t significantly impact the outcome.

In business writing, the goal is usually to be clear, concise, and actionable. If a document or discussion gets bogged down in “dancing on the head of a pin,” it means the writer or participants are losing sight of the bigger picture and wasting time on trivial matters instead of focusing on the core objectives. This can reduce productivity, slow decision-making, and frustrate stakeholders who are looking for straightforward solutions.