'Let me give you some constructive feedback...'

What is effective feedback. Does it actually exist? And why are we trying so often to formalise it?

Like many others, I have personally been on the receiving end of some feedback, that I experienced as harsh and, if I am honest to myself, at times even unpleasant. And, I am someone who, in a work environment, very much welcomes feedback, (perhaps paradoxically) mostly so when it is drawing attention to areas where I can improve whatever it is that I am receiving feedback about.

This made me wonder about the nature of feedback, what makes it effective and what does the very opposite. And also, whether feedback by close friends on a personal matter is different from what we receive at work, since it seems that my experience tells me it is very different.

So, I am dedicating this week’s article to feedback in its widest context.

To explore this, I would like to get clearer on these questions.

What is feedback?

Do we actually need feedback? (Spoiler alert: yes!)

How do we best incorporate feedback in our lives?

What is feedback?

In order to discuss feedback we must have a decent understanding of what we mean by ‘feedback’.

Let’s start with what Merriam-Webster dictionary’s definition of feedback is:

DEFINITION version 1 - Feedback is the transmission of evaluative or corrective information about an action, event, or process to the original or controlling source.

This is an expected definition that works very well generically. But, since in the context of this article the original or controlling source is a human being, I would like to enhance this by what psychologists make of this (they after all specialise in the human mind).

And, psychologists suggest to look at feedback from 2 different perspectives:

Intrinsic feedback. All the information one receives naturally, such as vision, audition, and from the process of (conscious and unconscious) self-perception (what psychologists call, proprioception1).

Extrinsic feedback. All the information provided over and above intrinsic feedback by another person, often a teacher, coach, colleague or (close) friend, etc.

Others can perceive that the intrinsic feedback that people receive and then process for themselves (perhaps including active self-reflection?), is not sufficient to achieve whatever they believe our joint objective is. The extrinsic feedback is then used as augmented feedback by the external person to complete their perception of the required feedback.

Looking at this from a human perspective, therefore, adds at least another dimension to our definition.

DEFINITION version 2 - Personal feedback is the transmission of evaluative or corrective information about an action or event by self-reflective processes, augmented by information provided by another person.

Let’s use this as the definition for this article.

Do we actually need feedback?

Building on DEFINITION version 2, it seems useful to me to look at tools and techniques that cognitive psychologists might use to better help us understand the relationships between us ourselves and others and what we can learn from them about the process of giving and receiving feedback.

One of those tools that I find very helpful to explore whether feedback is -in fact - useful and required (or perhaps not), is the Johari Window (extra points for those who understand where the name Johari originates from 😉).

The Four Quadrants of this window can be described as such:

Arena/Open

The Open area is that part of our conscious self – our attitudes, behaviours, motivation, values, and way of life – that we are aware of and that is also known to others. We move within this area with freedom. We are open books.

Façade/hidden

Information that is recognised (and/or created!) by us ourselves, but not known by any of our peers. These are things others are either simply unaware of, or that are untrue but for our own claim. This, by their very nature, includes accidental untruths or deliberate lies we might tell.

Blind Spot

Information that is not recognised by us ourselves, but that our peers do recognise and acknowledge. This information represents what others perceive but that we ourselves do not.

Unknown

Information that is neither recognised by us ourselves nor by our peers. They represent our behaviours or motives that no one specifically recognises – either because they do not resonate with our experience or because of collective ignorance of this information.

Allow me to explain -via a little bit of theory - why I believe how this simple Johari Window can help us understand why giving and receiving feedback is so important. This comes back to the conversational model I discussed in an earlier article as Complex Responsive Processes of relating2.

In the context of this article, the complex interactions of gesturing and responding is, de facto, a continuous sense making process via exchanging of the information we talk about in the Johari Window above.

This leads me to the following logic.

I see that the intrinsic feedback processes are at the basis of the theory of mind, or -in other words - that how we model other people’s behaviour guides our own chosen interaction with these others.

Clearly, we can only do that in the Arena and/or the Façade domains in the Johari Window, simply because -per definition - we are unaware of our Blind Spot or the Unknown domains.

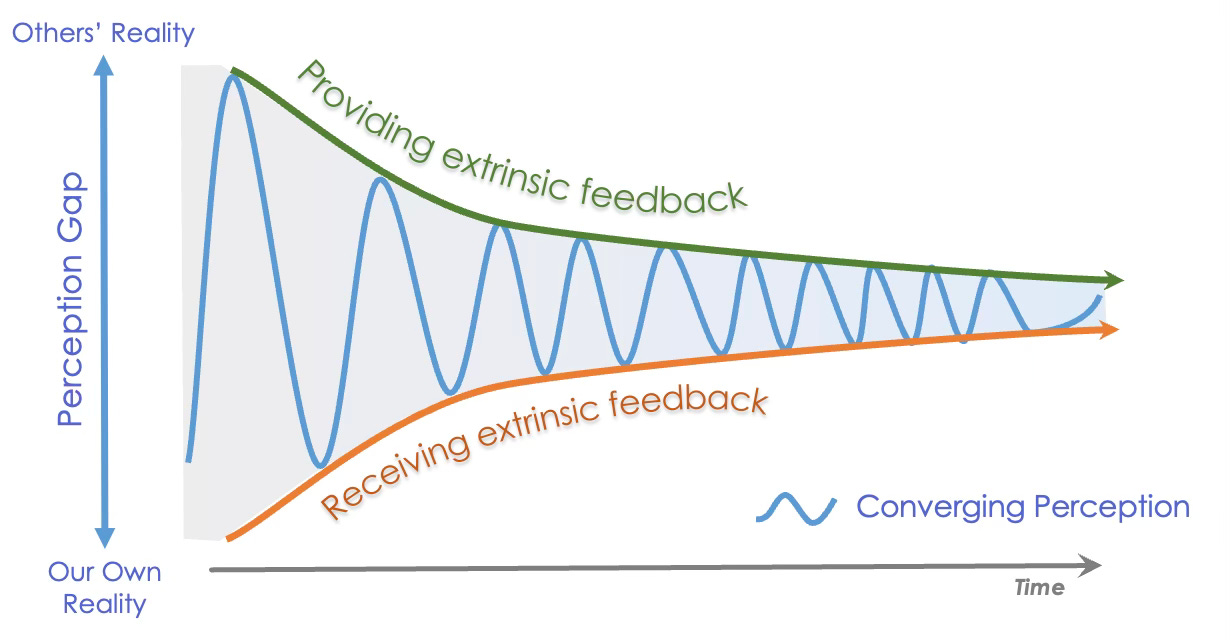

By choosing to provide extrinsic feedback to the other individual to augment their self-image, we introduce the possibility to lift the veil of their individual Blind Spots and expand their self-awareness.

At the same time, by being open to receive and internalise that feedback from others, we ourselves will expand our self-awareness and this then makes we can choose to adapt our own behaviours and interactions with others to better achieve our, individual and collective, objectives.

Without extrinsic feedback it surely must be much more challenging to achieve a form of convergence, or even reconciliation, in our conversations.

Converging, reconciled, conversations are pivotal for effective action to emerge in the context of whatever we try to do together (something we already concluded in the recent article about leadership).

This leads me to postulate the following conclusion that -I am sure - most of us intuitively already knew to be true:

CONCLUSION 1 - Giving and receiving feedback in imperative for effective and efficient action to happen in our day-to-day, work or private, lives

An important conclusion, of course, under the assumption that the reason why we often communicate is to enable effective and efficient action to emerge. For me, that is a given in a business context, but that might just be the challenge when we are talking about our private lives. After all, what does effective action mean in our private world?

I leave the reader to contemplate that for their own circumstances.

How do we best incorporate feedback in our (business and private) lives?

Because indeed in many business organisations effective and efficient action is seen as very important, particularly also to achieve high performing teams, there are often very formalised processes in place to solicit and obtain feedback. Indeed, if you do an internet search for ‘formal business feedback processes’ you get inundated with articles from Harvard Business Review (HBR), Forbes and the likes. People that know me, know my relatively guarded opinion of that type of articles.

As part of my consulting practice I have helped multiple large, global client organisations implement Performance Management solutions that always include an evaluation element containing formal regular performance review sessions (what about twice a year?) and 360 Feedback. Indeed, doing a search on 360 Feedback, again, provides a plethora of the usual suspects’ sources of how and when to do them, what questions to ask, and so on and so forth3. Can feedback really be so linear? (Quite apart from that, though, it apparently is good business to offer these services and thoughts 😉.)

What intrigues me about this all, are at least the following observations:

Apparently feedback is seen as important enough to spend active time and money on

But, somehow the feedback processes are seen as separate from the day-to-day conversations

Holding formalised feedback sessions is often included in some form of performance indicator for a specific manager, department or even entire organisation.

The latter observation I find particularly fascinating. The consequence of it being seen as something that needs to happen (and therefore needs measuring!) as a dedicated, separate activity, leads to the (say) twice yearly scramble to book feedback/performance review sessions in order to not negatively skew the KPIs. The purpose, of course, is still to improve effectiveness and efficiency, but in my experience it has often become much more of a box ticking exercise, full of platitudes and -quite frankly - mostly meaningless statements. Not surprisingly, often these formalised processes do not achieve more than people feeling good (or bad, for that matter) about themselves twice a year.

CONCLUSION 2 - The way formal feedback is incorporated in business organisations, very often does not lead to any improved effectiveness and efficiency or actual better performance, but seems to exist mainly to ensure we meet the required reporting requirements on Performance Management.

So, perhaps this is not the way to go about it. Yet we do (and consultants like me can earn decent money on the back of it!).

I would like to offer an alternative way to think about feedback. And, not surprisingly, it comes back to my preferred model to see organisations as conversations. (Yes, dear reader, there is a clear theme emerging here).

My suggesting is to stop looking at giving and receiving feedback as a formalised process, that is somehow separate from our normal day-to-day interactions. Instead, let’s agree to collectively incorporate the feedback open and honestly in our already ongoing conversations. And we can do that by agreeing some very simple Rules of the Game for our conversations that we can hold each other accountable to.

Things like:

We will always communicate openly and honestly (this creates trust and minimises the Façade in the Johari Window)

We will always communicate respectfully and if we feel differently, we will be encouraged to say so

We will listen to others with an open mind, and not presuppose bad intention (this avoids us being blinded by the Blind Spot in the Johari Window)

We will not judge other people’s views or ideas, but instead share our own experiences, thoughts and/or feelings on the subject (instead of starting a sentence with ‘this is nonsense’ or ‘this is not true’, start with ‘this is not my experience, because mine is…’, etc., you get the drift; after all, someone’s experience is what it means for them and that cannot be meaningfully challenged by saying ‘that is not yet your experience at all!’)

If something makes us feel uncomfortable, we can say this openly and invite others to explore that with us (Perhaps say thinks like ‘what you say makes me feel very uncomfortable, can you help me understand why that could be?’)

We keep asking ourselves and the people we are in conversation with, if here is anything we could be missing, perhaps by deliberately involving people from outside our usual group. This is one reason why we could do peer reviews with other organisations to help remove our own blindfolds, for instance. (We do this to explore whether there are any Unknowns, as per the Johari Window, that could inhibit what we are trying to do together)

Depending on our cultural and personal backgrounds these rules will of course differ greatly. My strong suggestion is, though, that it is important, that we agree this type of Rules of the Game in the first place. The conversation around those can already by very enlightening in itself. And, these rules are never plastified or put on unchangeble posters on the wall. These rules need to be dynamic. Regular ask ourselves the question ‘are these rules still working for us?’, ‘do they make the conversations better, more effective, or not?’ and we change them collectively when appropriate as we go along.

My experience is that, over time, these rules become part and parcel on how we collectively choose to (sic!) interact and at that stage we can stop talking about Rules of the Game as we now naturally live by them. And here, again, the role of leaders on every level in the organisations is pivotal. These are the people that can draw attention to the rules not working, or people perhaps not understanding what we have agreed, and so on. Another convergence process!

CONCLUSION 3 - We can start to incorporate feedback into our normal day-to-day conversations as a matter of course. We can do that by starting to agree some basic, dynamic, conversational Rules of the Game that will eventually lead to feedback becoming indistinguishable from all our other conversations.

This resonates with me, because isn’t this how we normally operate in our personal lives with our friends, families, etc? Of course, we usually don’t make those rules explicit, and my personal reflection is that that caused me to feel to uncomfortable about the personal feedback I received, referred to above. Perhaps those that gave the feedback did not respect some basic unwritten Rules of the Game, that for me clearly existed? Or pehaps, I should have been much clearer up front about how I felt about the situation we were in? I will take this intrinsic feedback onboard and with the given extrinsic feedback, we will move further down our own converging perception curve.

You could, of course, ask now whether, if this works so well, it means that there is no place for formal feedback and performance review sessions? Well, not necessarily. We can use the formal interventions as events on our converging perception curve. A corporate way, if you like, to have the continuous conversation. As long as we don’t start believing, that the formal externalised process is all there is. If we see it as an integral, not separate, part of the overall conversation that is our organisation, we will be able to thrive.

And, finally…

… I would like to go back to the very beginning of this article. To MC Esher’s drawing. In his own wonderful way, Esher shows a waterfall miraculously feeding itself, seemingly defying gravity. But what if what Esher is really showing, is the ability for us as people together to create our own gravity rules? That we can build our own reality that ensures that feed and feedback are one and the same thing?

I like that idea very much.

What is your experience with feedback? In your work and/or personal lives? Do these experiences differ?

Can you share experiences where companies do this very well? And, if so, what makes that so effective?

Conversely, what experiences do you have where it did not work at all? And, what can we learn from that?

Proprioception as defined by wordnik:

The unconscious perception of movement and spatial orientation arising from stimuli within the body itself.

The sense of the position of parts of the body, relative to other neighbouring parts of the body.

The ability to sense the position and location and orientation and movement of the body and its parts.

Stacey, R. (2000). Complex Responsive Processes in Organisations, London: Routledge

It even includes, very mechanical, notions of a feedback decision tree, for instance (Cameron Conaway, HBR, 14 June 2022).